A look inside James E. Pepper Distillery

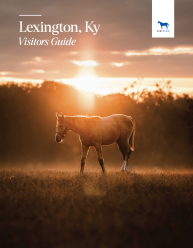

On the subject of bourbon, words like tradition, heritage and history are thrown around a great deal. While context is everything, you must start in the heart of the Bluegrass region to really get the full story. The motherland I’m referring to is Lexington, Kentucky. It’s here that the first handful of distilleries were ever registered with the United States government. Today, the oldest Kentucky distillery is revitalizing an area of town known as the Distillery District—James E. Pepper Distillery.

As the complex is now also home to delectable destinations such as Goodfellas Pizzeria, Crank and Boom Ice Cream, Ethereal Brewing and Middle Fork Kitchen Bar, you could easily eat and drink your way through a good portion of the day in the Distillery District. But no visit would be complete without touring the distillery’s new digs.

This place is much more boutique than the big boys. You won’t spot rick houses perched atop rolling hills. There are no massive assembly lines, except maybe on bottling day. By massive, I mean a couple of guys numbering the labels after they come off the bottle line.

Ben was my tour guide the day I explored how deep the roots of James E. Pepper Distillery actually run. We gathered in the tasting room, and headed into the living history museum, um… I mean distillery.

A HISTORY LESSON…

The Pepper story originates with James’ grandfather, Elijah. He was a farmer who began distilling during the American Revolution. Ben pointed to many of the old bottles with the date 1776 inscribed on the labels––a nod to the whiskey’s humble beginnings. Elijah built his first Kentucky distillery in 1812 on the property now known as Woodford Reserve. His son, Oscar, ran the distillery for about 50 years. To this day, you can explore Pepper artifacts, because the fine folks at Woodford work hard to preserve the legacy.

Oscar gave his son, James, the distillery at the age of 15. Here’s the thing, 15 was 15 no matter how hard you scratch your head. What in the world would a teenage boy do with a distillery? Well, they run it into the ground. That’s when Woodford bought it from Pepper and eventually became a household name when it comes to premium, straight bourbon whiskey.

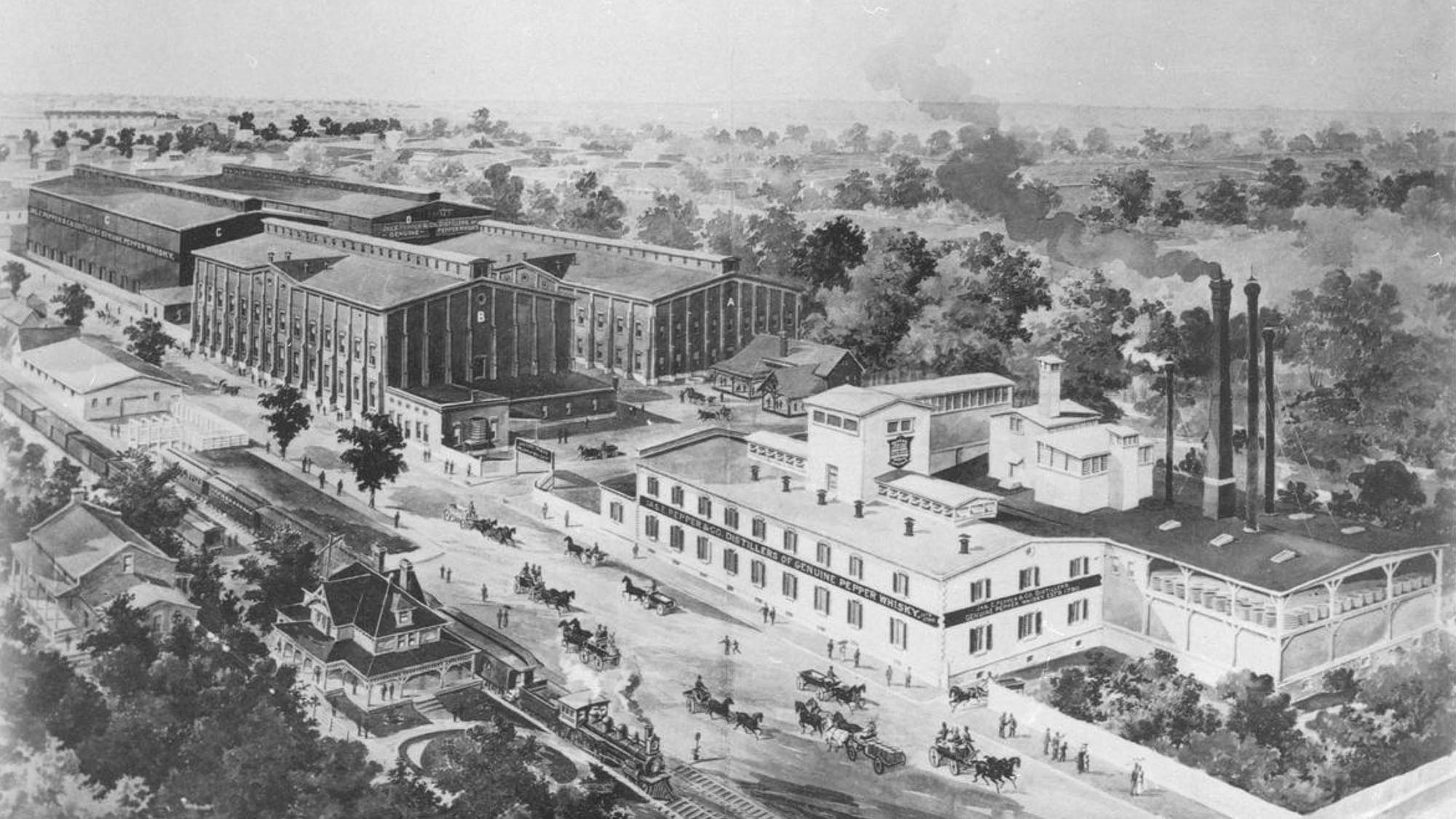

James built his first distillery from the ground up on the current site in 1879. You can see an illustration of this Manchester Street property in the museum. You might notice quite a few rick houses in the illustration. This is because back then, Pepper was one of the most popular bourbons on the market.

Through the turn of the century, the Peppers were flamboyant in their promotion. “The Oldest and Best Brand of Bourbon Made in Kentucky” the labels boasted. James and his wife, Ella, would travel all over the country in a decked-out train car he called “Old Pepper” promoting the brand. They spent a lot of time at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City entertaining prominent families like the Carnegies and the Roosevelts.

On one such occasion, he brought a Louisville recipe up for them to try and “The Legend of the Old Fashioned Whisky Cocktail” was born. Even though he didn’t come up with the actual recipe, he was accredited for it, due to his prolific branding. You can read the original recipe in the museum, but good luck on trying to recreate it. The measurements are shall I say, off?

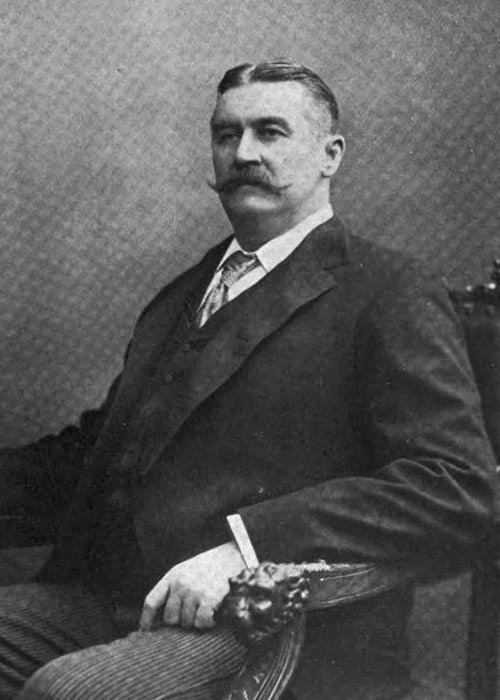

(on the left)

(on the left)

Colonel James E. Pepper and his wife, Ella a.k.a Queen of the Turf, not only worked in the distilling industry, but they were key players in the horse racing industry that would eventually save them from a second financial failure.

Ella ended up raising enough money through horses to bring the distillery out of foreclosure earning her the title “Queen of the Turf.” When she sold the distillery to investors, she became the wealthiest woman in the state of Kentucky for her time. She took that money and traveled the world. But, only after James “slipped” outside the Waldorf one rainy night and died due to complications from his fall.

The investors continued to produce the whiskey even during Prohibition for medicinal purposes only, of course. During that time, you could buy one pint of whiskey per week. There were over 6 million prescriptions for a state with about one million people. You do the math. Ben joked about every kid in the family suffering from night blindness, and some family members that didn’t even exist.

The point is that Prohibition was not the demise of James E. Pepper Distillery, fashion and trends were. They produced up to 1933, one year prior to the end of Prohibition when the distillery mysteriously burned. Well, not so mysteriously, I suppose.

One year later, they rebuilt in 1934 which is the complex you’ll see when visiting the Distillery District now-a-days. When clear spirits like vodka and gin became all the rage during the 50s, distilleries began shutting down nationwide, including James E. Pepper Distillery in 1958.

THAT WAS THEN, AND THIS IS NOW…

The distillery was in complete disrepair when the abandoned trademark was picked back up in 2008. The brand’s new owner, Amir Peay, started working with distillers in the area to resurrect the recipe. In 2016, Peay signed a deal to bring Pepper back to its original home, and in December of 2017 distilled and filled the first barrel. It’s Peay’s goal to produce one hundred percent of the product onsite from here on out—mark your calendars as this barrel will be ready around 2020.

Upon entering the new space, the James E. Pepper Distillery sign reads “DSP-KY-5” which designates which distilled spirit plant you are at and its Kentucky number. That number gets retired and can’t be used by another distiller. If you were to open a distillery today, your number would be in the 20,000 range. “By coming back to the original distilling site, using the original recipes, and perhaps a bit of begging and pleading, the state reissued us the retired number,” Ben explained.

Speaking of government, as of 1965, Bourbon has been the official national spirit declared by the United States government. In fact, there’s congressional guidelines called ABCs: American made, Barrel must be brand new, charred and white oak, and Corn must measure at least 51% of the grain content.

WATER, GRAIN, FERMENTATION, DISTILLATION, AND MATURATION.

Maybe by coincidence, but the number five is also special because it is the number of essential parts to making a fine whiskey––water, grain, fermentation, distillation and maturation.

Water

Town Branch Creek literally runs under the city and along the distillery but is no longer a clean source due to its city use. However, there’s a well nearby which is why Pepper stuck his flag in this specific location. Ella described the well as nice, clean, limestone Kentucky water to a New York Times reporter, once. So, when Amir resurrected the place, he dug 200-feet deep to that original well which is the source of his award-winning whiskey.

Grain

There’s an old stone mill that greets you upon entering the grainery which is believed to be the original mill. These days they use a large hammer mill. As a small production, they are able to get 80% of their grain locally at Gilkison Farm, while 100% of their corn is from this farm.

Fermentation

The grain is smashed down to a fine mill prior to heading to the cooker. Yeast is then added to start the fermentation process. You can actually taste from the cooker when it’s cooled. It’s sweet like breakfast cereal. The mixture is then dumped into the tanks to ferment. After about 24 hours, it starts to ferment. It’s not until tank 4 that the 48-hour ferment reveals something like a sour beer. This liquid is known as sour mash or distiller’s beer and is only 24 proof. Tank 5 has coils in it where cool, well water keeps the mash from getting too hot. If it gets too hot the fermentation ceases. “I want 24 proof whisky” said no one. The fermenting tank then feeds the liquid through red hoses into the still.

(on the left)

(on the left)

Distillation

The still has yet to be named, but is from Vendome Copper & Brass Works––the original still maker. I personally think they should name her Ella, but they didn’t ask me. This column still allows the mash to fall one level at a time. As the steam rises, the alcohol vapor rises to the top. The condensers take over, with the cold well water condensing the vapor back to liquid at 115 proof. It’s then refined during a second distillation at 130 proof moonshine.

Ben invited me to the tasting table where he poured unfiltered corn oil into the palms of my hands and asked that I rub them together. I smelled the grains in my warm hands. He then poured a glass to teach me how to properly taste whiskey.

I smelled with my mouth open, so the fumes didn’t burn my nose. I took a small sip and washed my palate by rolling the clear liquid around on the top of my tongue where all of my taste buds meet. They call this “the Kentucky chew.” As soon as my tongue started to burn, I swallowed and exhaled, as opposed to inhaling. Inhalation will cause that crazy cough you may have experienced and thought you couldn’t handle spirits. I didn’t taste anything on that first sip. The second sip was where I actually tasted the character of the bourbon. And, then on the third, I looked for something new.

Maturation

To be considered a straight bourbon whiskey, the spirit must sit in the barrel for at least two years. Most affordable straight bourbons found at your favorite bottle shop sit in the barrel around three to four years. Anything five and up and becomes pricier.

The climate fluctuations in Kentucky help flavor the bourbon—hot summers and cold winters push the bourbon in and out of the oak. You’ll want to shoot for 10-20 years for the best aged bourbons.

Ben then offered a thief full of straight rye whiskey with no corn from the barrel. I tasted eucalyptus, cinnamon, clove, anise and cardamom on that third sip. The James E. Pepper Barrel Proof Rye is 115 proof and is their biggest award-winner.

Because I “stole” from the barrel with a thief, Ben suggested I sign the barrel. You’ll find my signature, along with a plethora of other “thieves” signatures, on that barrel when you visit.

He invited me to the tasting table where 100 proof rye and bourbons which are their nationwide best-sellers. The proof is lowered with the addition of water, which blooms the flavor profiles. Caramel, butterscotch, leather and tobacco notes are found in this bourbon. It reminded me of the very best dessert wines, but with a Kentucky hug on the end.

Finally, Ben offered me a whiskey chocolate which is something most any distillery will offer. But, this one became my new favorite from DB Bourbon Candy made with James E. Pepper Rye.

Back in the front tasting room, I snagged one of the remaining bottles of The Old Pepper 10-year Single Barrel Bourbon which was only a 15-barrel production made for their grand opening. If there’s any left when you visit, go ahead and indulge. After all, there’ll never be another like it.

You can also find James E. Pepper in an array of locations including Lexington area restaurants and bars like OBC Kitchen located at the Lansdowne Shoppes. Their Bourbon menu reads like a Who’s Who of Distillers. Joints like OBC don’t mess around when it comes to their medicinals. That’s why when they invited me to a private barrel select over at Jim Beam, I said “Hell, yeah!”

Knob Creek is one of Jim Beam’s small-batch bourbon labels. That’s the bourbon we would be tasting for the barrel select. We were shuttled from the distilling facility up on the hill to “WHSE K” which was built in 1951. When the doors were flung open, I swear I could hear those angels singing a few bars from The Wooks “Glory Bound” album. You know how those sneaky winged creatures sip up their fair share of each barrel. Ours only had about 1.5 gallons missing when it was all said and done. So, not too many fallen angels after all.

Hunter Davis is the Beam Barrel Specialist. He walked us through the selection process that goes something like this: tastings happen at barrel strength and are selected from three separate barrels. The first sip is at barrel strength, prior to adding a little distilled water on the second round. It’s helpful to eliminate your least favorite right off the bat, while your palate is still fresh. Let the whiskey breathe prior to the second sip. Think about how you’re going to pour the whiskey. Are you going to make cocktails out of it, or are you going to serve it neat, up or straight up? This will dictate the tasting notes you are exploring.

There will be a couple of rounds of tasting. So, take your time. The one we collectively chose had quite a bit of pepper finish to it. Its nose was smokey and dense. Because it came straight from the barrel during tasting, I found char in the bottom of my glass, which was a good thing indeed.

After a bit of bung hammering, barrel signing and other shenanigans, we headed back down the hill for the bottling process. Our 14-year-old barrel of Knob Creek Bourbon yielded 17 cases of six-packs for OBC. Not a bad haul, y’all!

Back at OBC, if you only order one thing to pair with your favorite bourbon, get the “bacon in a glass.” I know it sounds simple. That’s because it is. Call me crazy, but something about bourbon glazed bacon with a side of peanut butter dipping sauce says “butter my butt and call me a biscuit” to me. Now, that’s beyond grits in a major way. Don’t ya think?