The myth of an empty Kentucky – one perpetuated by land speculators in the late 1700s – has had a lasting effect on people’s understandings and beliefs about the presence of Indigenous Americans in the state. Many different tribes once called Kentucky home, including the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, and the Shawnee. The Shawnee hunted and lived in the Bluegrass Region. These clans were a part of the larger Shawnee tribe who lived in the Ohio Valley with most of their major villages and settlements being in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

It is likely that no major indigenous settlements were in Kentucky. However, the archeology of the state – from rock art, cave paintings, arrowheads, and ancient pottery shards – prove that Indigenous Americans lived throughout the state prior to European contact. Indigenous Americans were forced from their homelands, including Kentucky, because of European settlers. This came in the form of European settlements and conflicts and eventually more centralized tactics including Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears. Today, Shawnee Tribes in Oklahoma, including the Eastern Shawnee, claim Kentucky as one of their tribe’s original homes.

Prior to 8,000 BC

Paledonians lived in Western Kentucky and eventually migrated eastward, settling in central and eastern Kentucky. Paledonians were Clovis people, meaning they used tools, and were hunter-gatherers. They moved in groups of 15-20 people hunting mammoths and mastodons. Archeological evidence from this era indicates that Paledonians stayed close to Kentucky rivers for water, freshwater fish, and shells.

For the next 7,000 years, from 8,000 BC to 1,000 BC, indigenous Americans continued to live in Kentucky. Archeologists have named these Paledonian descendants Archaic peoples. As the Ice Age ended, Kentucky’s climate became milder, with summer lasting longer. As these peoples were also hunter-gatherers, no permanent settlements were used. Indigenous Americans during this time, however, valued Kentucky for the fauna in the region – deer, elk, bears, rabbits, squirrels, and raccoons.

By 1,000 BC, the climate of Kentucky was similar to the climate in the state today. Population sizes of Indigenous Americans grew. Although these peoples still moved with the seasons, they began to move less frequently and began returning to locations because they started gardening.

1,000 BC to 200 CE

This is known as the Woodland Period. While the Indigenous Americans in Kentucky were still hunter-gatherers, they stayed longer at settlements and tended to return year after year to the same places. They experimented with gardening and farming, even using controlled burns to kill weeds and enrich the soil. In Eastern Kentucky caves, Woodland Indigenous Americans domesticated the earliest sunflower and goosefoot. As they learned varying plant and harvest cycles, they tended to stay all year if the food they planted could last them.

This time period is also when Adena Culture became prominent. The Adena were mobile hunter-gatherer-gardeners who lived in groups of 15-20 people, usually made up of extended families. Archeology has been able to tell us much more about Adena culture than the ancestors who came before them. The Indigenous Americans living in Kentucky during this time traded both locally and non-locally, archeologists having found marine shells from the Atlantic coasts in Kentucky and barite and limestone from Kentucky has been found along the coast. The Adena used Kentucky limestone to make pottery, which helps them stand out from their ancestors.

Following the Adena period, Fort Ancient culture lasted from 900 CE to 1750 CE which includes early contact with Europeans. Fort Ancient peoples were no longer true hunter-gatherers. They still hunted and gathered but they lived in permanent settlements with gardening and early agricultural technology, including crop rotation and controlled burns.

During this period, the first interactions with Europeans occurred. Although the Spanish were in what would become the United States in the 1500s, there is no documentation of Europeans in Kentucky until the 1730s. There is evidence, however, that Indigenous Americans at this time were aware of Europeans due to regional trade networks, including Kentucky peoples participating in the deer skin trade with Europeans.

Modern Era

This modern era was also marked with a reduction in Indigenous Americans living in Kentucky. Inter-tribal conflicts, like the Beaver Wars throughout the seventeenth century, saw the Shawnee, who had lived in Kentucky for hundreds of years, forced by the Iroquois to leave in large numbers to the south and west. Small numbers of Shawnee remained in Kentucky but there were no large villages and settlements. The Iroquois did not settle in Kentucky either, preferring to hunt there and live farther north.

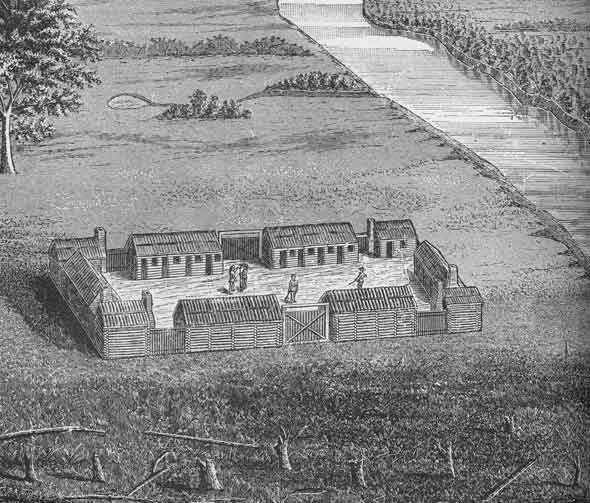

Because of the barrier of the Appalachian Mountains, European spread to Kentucky was slower than along the East Coast of the modern United States. At the outbreak of the Seven Years War (sometimes called the French-Indian War) in 1754, Kentucky was still known as “Indian Country.” The tribes living in Kentucky and the broader Ohio Valley – the Shawnee, the Cherokee, the Mingo, and Tutelo – had frequent face-to-face interactions with Europeans, which were almost exclusively about the fur trade until the mid-1700s. When Europeans, including Daniel Boone, realized that Kentucky was fertile, forested, and what they assumed to be empty, more and more Europeans attempted to settle in Kentucky. The first settlement in Kentucky was Ft. Harrod in Harrodsburg in 1773. This fort, and many other settlements in the Bluegrass Region quickly learned that Kentucky was not “just a hunting ground.”

In 1762, the British negotiated a “peace” with tribes living on or near the Ohio River. The Iroquois wanted a dual withdrawal of French and British settlers but the British stayed. They also wanted a restoration of trade but there were several problems including the scarcity of goods and their high prices.

British settlers continued to encroach and go over the negotiated bordered lines that separated British and Indian lands.

In Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1769, the Iroquois ceded all the land they claimed south of the Ohio River. The treaty set the river as the boundary (Iroquois to the north, British to the south) leaving Kentucky to be settled and legally blocking the Iroquois, Shawnee, and other tribes from hunting there.

In 1772, the Cherokee surrendered their claim to Kentucky to the colony of Virginia. Colonial land surveyors went to Kentucky to begin settlement and skirmishes broke out. Lord Dunmore’s War broke out in 1774—prelude to native-colonist fighting that coincided with the American Revolution.

In the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775, the Cherokee sold their land to the Transylvania Land Company. Settlers began flooding in even greater numbers to Kentucky with families, slaves, livestock and seeds, and belongings, transplanting their colonial way of life west of the mountains.

Throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s, Kentucky settlers wrote widely about the hostile native peoples who lived nearby. This period was marked by skirmishes between settlers and tribes. Many early Kentucky settlements were fortified villages to protect from attacks, like Boonesboro, Fort Harrod, and even Bryan’s Station in Lexington.

During the war

During the American Revolutionary War, indigenous tribes fought with the British against American colonists. Several native-colonist conflicts took place in Kentucky, including the siege of Boonesboro, attacks on Martin’s and Ruddle’s Station, and the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782.

Leading to the Battle of Blue Licks, the attack at Bryan’s Station occurred. Four brothers from North Carolina settled three miles north of what is now New Circle Road and named it Bryan’s Station. Forty log cabins withstood several native attacks. In August 1782, Bryan’s Station was besieged by Wyandots, Lake Indians, British Canadian rangers, Shawnee, Delaware, and Loyalists. According to Daniel Boone, who was Lieutenant Colonel of the Kentucky military at the time, there was a force of 400-500 troops. Back-up militia led to the Battle of Blue Licks (60 miles away in Robertson County). The backup Kentucky militia included Boone and Richard Mentor Johnson (who allegedly killed Tecumseh) and was made up of 47 men from Fayette County and 147 men from Lincoln County. The battle was a defeat for Americans, although the surrender at Yorktown had occurred months earlier.

After the War

By the end of the Revolutionary War, there were around 12,000 settlers in Kentucky and 72 settlements were in the Lexington area. Treaties were signed but stolen land and retaliatory raids continued.

In 1792, Kentucky was admitted as a state. Fighting between settlers and natives continued. The Battle of Fallen Timbers and the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 brought the long period of conflict in Kentucky to a close but distrust and resentment continued.

1,000 Indians from many tribes attended the treaty conference. They believed the treaty meant that they could live forever in the places where they were then living (northern Ohio, Indiana, and southern Michigan). However this was one of the first steps towards Indian relocation and acquiring all lands east of the Mississippi.

The treaty established an annuity system which meant yearly payments made to tribes for leaders to distribute among their people. It also declared that the American government had influence within tribal government and that the US government was committed to “civilizing” American Indians.

Two important trends were happening nationally.

- Movement to transform American Indians into civilized American citizens

- Movement to remove all American Indians from lands east of the Mississippi River

A part of the movement to make Indigenous Americans “civilized” were schools for native children. The Choctaw Academy is one example of this.

The Kentucky Baptist Mission Society opened a school for Native American boys in 1819 on land owned by Richard Mentor Johnson in Scott County.

In 1825, the Choctaws in Mississippi asked that the money for their land go toward creating a school to educate tribal boys to live in “the white man’s world.”

In 1825, there were 25 Choctaw boys enrolled at the school. By 1835, 188 students from 10 different tribes (Choctaw, Creek, Pottawantonic, Cherokee, Sac and Fox, Ottawa, Miami, Quapaw, Seminole, and Osage) and even some white boys were taught English grammar, reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, surveying, astronomy, philosophy, history, and music. In later years, the school taught more vocational classes.

The school eventually closed due to lack of funds. Many of the tribes who sent their sons to the school were forced to move west to present-day Oklahoma and no longer wanted to invest in the school.

The school was located in Great Crossing (Scott County) a historic community founded in 1783 where buffalo herds once crossed North Elkhorn Creek. General LaFayette visited the school in 1825.

The presence of the school in central Kentucky was due mostly to Richard Mentor Johnson’s political importance and ability to get good deals from the government. The school allegedly helped him get out of debt.

Following harsh national legislation of Indian Removal and the infamous Trail of Tears, Kentucky’s Indigenous American population dwindled rapidly in the nineteenth-century. The frequency in which artifacts are found throughout Kentucky – from pottery shards to arrowheads – the myth of an empty Kentucky is easily put to rest. Several sites throughout the state continue to be of archeological importance, including sites in the Eastern Kentucky Mountains and caves, the caves of Western Kentucky, and the mounds of the Adena culture throughout the Outer and Inner Bluegrass, including one located in Fayette County.

For more information, please visit Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission and the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology

Header image from Kentucky Historical Society: https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/items/show/596